Our Story

- Details

- Written by Mondy Lariz

- Category: allowcomments

- Hits: 3287

TIMELINES July 31 2002

Social Clubs Enlivened Claremont McKenna College

by Terry Carter

In all seriousness, I do admire Claremont. Any part of the Inland Empire where I can stand for 10 minutes without having my cultural illusions shattered has my respect. The mix of used books, rare musical instruments, sidewalk cafes and, of course, the dog park makes "The Village" a great hangout. Maybe it's the almost French name. Maybe it's all those colleges -- so many that it's easier just to refer to them in the collective. Maybe it's just my own nostalgia. No, it must be Claremont.

Not that life has always been exactly placid there. Until World War II, there was the same quiet grove scene as in the rest of the Empire, although the colleges were a unique factor even then. Like all great schools, they were working hard at improving their reputation and image. The war brought the same influx of people to Claremont as to the rest of Southern California, plus an innovation that made more impact there, again because of the relatively larger academic community.

That innovation was the G.I. Bill, a federal law giving veterans financial help in furthering their education. That was a good thing -- a great thing, in fact -- but it had unforeseen consequences. It brought into the halls of academe a group of older people with vastly more life experience than your average college freshman.

In a way, the newcomers might have been expected to be model students. They understood discipline, after all. They had lived on tight schedules. They had seen enough of the down side of life to appreciate where education could take them if they studied hard.

Yet they were also experienced enough not to want to hold still for rules that seemed needless. They had just spent years living by the regulations, but they had also been learning how to shortcut those regulations where possible.

At Claremont Men’s College, as it was then, there was at first a generous move toward accommodation. The dean of students through the 1950s was William Alamshah, whom students called Baghdad Daddy because he was of Middle Eastern descent. (Never mind that he was Iranian-Syrian, not Iraqi.) Besides being a jazz trumpeter, Baghdad Daddy was a veteran himself, so his

philosophy toward his fellow vets was "live and let live."

Kevin Starr, California's premier historian, goes so far in his 1998 book "Claremont McKenna College" as to describe the Alamshah regime as frankly permissive.

In the 1960s, however, as the Claremont Colleges' collective aspirations continued to rise, so did those of student radicals around the world. Determined not to give ground, Claremont McKenna President George Benson brought Clifton T. MacLeod from the University of Rochester and made him Dean of Students, with a mandate to take some slack out of the leash.

MacLeod had his work cut out for him. His major headaches were three. First were "floating" TGIF (for "Thank God It's Friday") parties. Like "floating" crap games, TGIF parties had no permanent venue. They happened in orange groves, foothill glens, even vacant lots in town. The only thing that could be depended on was that alcohol would flow freely -- too freely for MacLeod and

the Claremont Police Department.

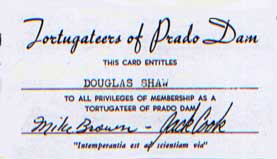

The other two villains were two social clubs, the Knickerbockers and the Tortugateers of Prado Dam, tortuga being Spanish for “tortoise.” They illustrate the different modes of revolutionary activity. The Knickerbockers were a well-dressed group, along the lines of preppies. Maybe that was natural camouflage; maybe it was a more subtle statement that appearance and behavior might be two different things.

Life was simpler among the Tortugateers of Prado Dam. To join, you didn't need a blazer, an ascot or the right shoes. All you needed was a hat. Any hat. A World War I campaign hat or a World War II "50 mission" hat would do nicely. (A "50 mission" hat derived its rakish shape and name from the fact that bomber pilots wore headsets over their hats. Doing this for 50 missions would definitely alter the hat's intended shape. Strictly speaking, it was non-regulation but considered very rakish.) Berets, Stetsons and baseball

caps worked just as well, however.

The Tortugateers thing worried the establishment. There was supposed to be some deep sexual innuendo there, but nobody could figure out what it was -- probably because there wasn't any. The Tortugas are simply an island group in the Caribbean, so inhospitable that mariners generally called them the "Dry Tortugas." Getting marooned there was a fate to be avoided, and the

Tortugateers' state of semi-dress could certainly evoke visions of castaways.

Here again is a lovely extended metaphor. The world is all a desert, a friend of mine once said -- only the amount of rainfall varies. The Tortugateers seem to have been calling attention to the self-perceived alienation of "The Lonely Crowd," a book by Vance Packard that many of them probably read.

Dean MacLeod wasn't as interested in how the Tortugateers perceived themselves as in how the world perceived Claremont in general and his college in particular. The administration generally failed to regard the Tortugateers' existence as something in keeping with their desire to raise their college complex to the level of Oxford or Cambridge.

Given that the Tortugateers were a semi-underground society, the dean was operating in the dark to some extent. He once threatened to expel them as a group, but could neither do that nor end the TGIF parties. The best he got was a name change to "Mara Togas," which goes unexplained.

By whatever name, then, the clubs and parties continued, but in retrospect, MacLeod ruefully admitted that while he was fighting these "evils," the quality of Claremont McKenna students in general was improving and that Knickerbockers and Tortugateers in particular turned out to be very supportive alumni.

TERRY CARTER is a historian who lives in Corona.

|

|

|